A while ago, as I was writing Buried Gods Metal Prophets I often looked back at my childhood games and wondered what they meant then. Whether time has given them a different meaning or not. It might have. And surely while the Guillemot editors worked on the manuscript, there were moments when my siblings’ chasing in the backyard or ‘soldier-soldier’-game felt untouched and sacred. Precious and private.

At first, sacred to me, and later just sweet reminders that childhood play and joy are universal experiences. A child’s laughter and falls and bruises and tears have a collective ‘sameness’ yet our experiences give them unique meaning. A bit like different interpretations of what ‘freedom’ and ‘enjoyment’ are all about. A bit like what being human is all about. After all, war and tragedy, love and disappointment, growth, learning, failure and success are human experiences that repeat themselves despite topological or temporal differences.

TU-PLEI is not just an invitation ‘to play’. It is an invitation to engage with the ludic self then to share the experience with others. TU-PLEI is an exhibition which brings together painting, photography, collage, prints, sculpture and montage from artists with a perceptive and individual interpretation on contemporary playfulness.

Alongside their artwork, there will be poetry from Buried Gods Metal Prophets. FREE entry!

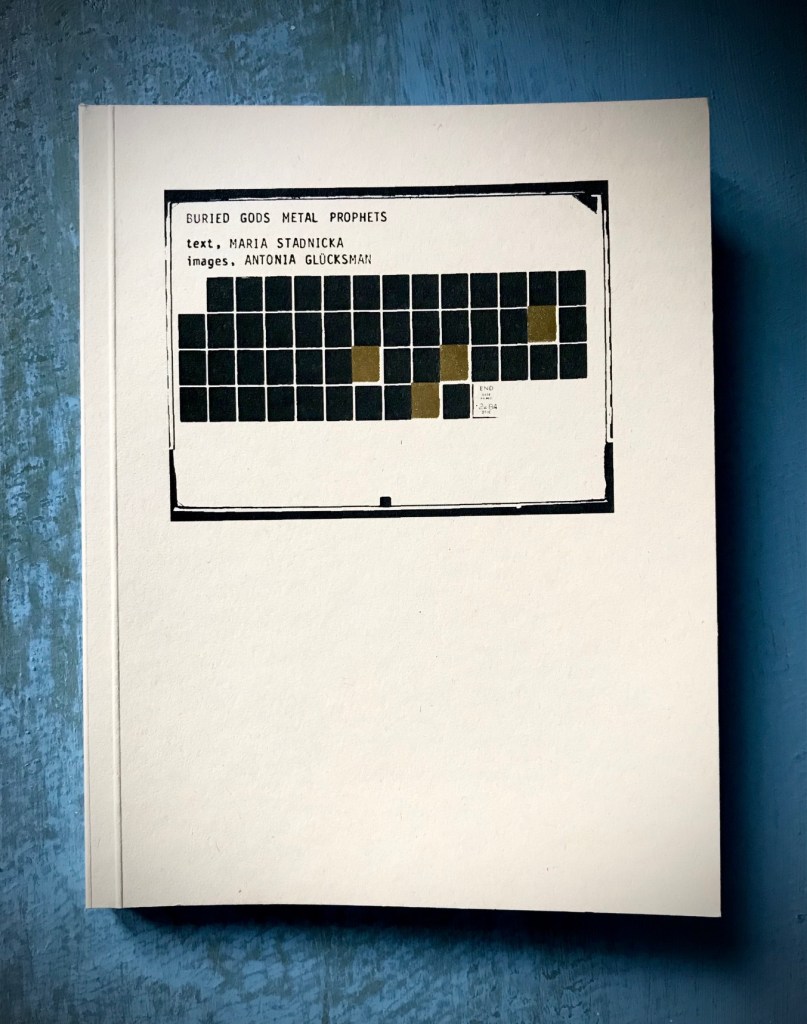

Buried Gods Metal Prophets published by the Guillemot Press, edited by Luke Thompson and Sarah Cave and illustrated by Antonia Glücksman is available here.

The exhibition will be open 20-25 July 2021 at Stroud Brewery.

‘Stadnicka’s fourth collection is inspired by the experiences of her siblings who lived in a Romanian children’s home during the time (1967-1989) when the Communist Party banned contraception and abortion. Around 12 million illegal abortions took place and over 250,000 children were placed in care homes and orphanages. The collection also draws on Stadnicka’s experiences as a teacher with HIV-positive children at a Romanian orphanage, and on interviews with women who performed illegal abortions. The book explores the effects of trauma and state oppression, as well as the realities of social, political and historical crises.

‘Stadnicka’s fourth collection is inspired by the experiences of her siblings who lived in a Romanian children’s home during the time (1967-1989) when the Communist Party banned contraception and abortion. Around 12 million illegal abortions took place and over 250,000 children were placed in care homes and orphanages. The collection also draws on Stadnicka’s experiences as a teacher with HIV-positive children at a Romanian orphanage, and on interviews with women who performed illegal abortions. The book explores the effects of trauma and state oppression, as well as the realities of social, political and historical crises.