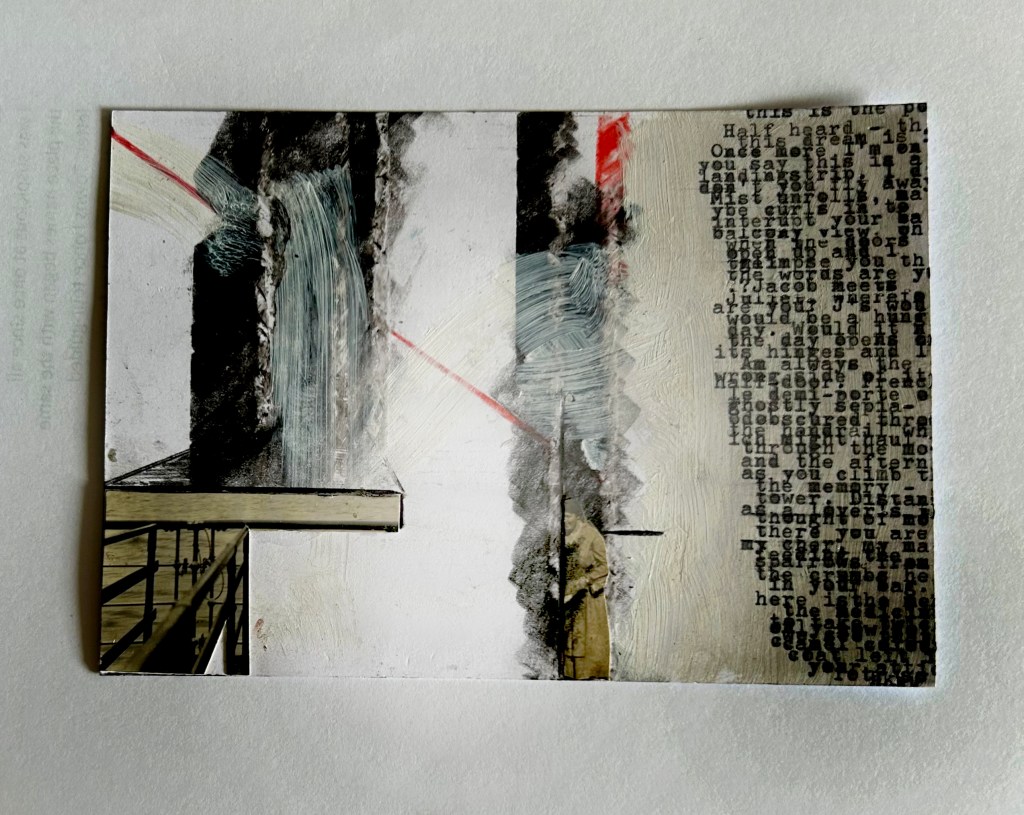

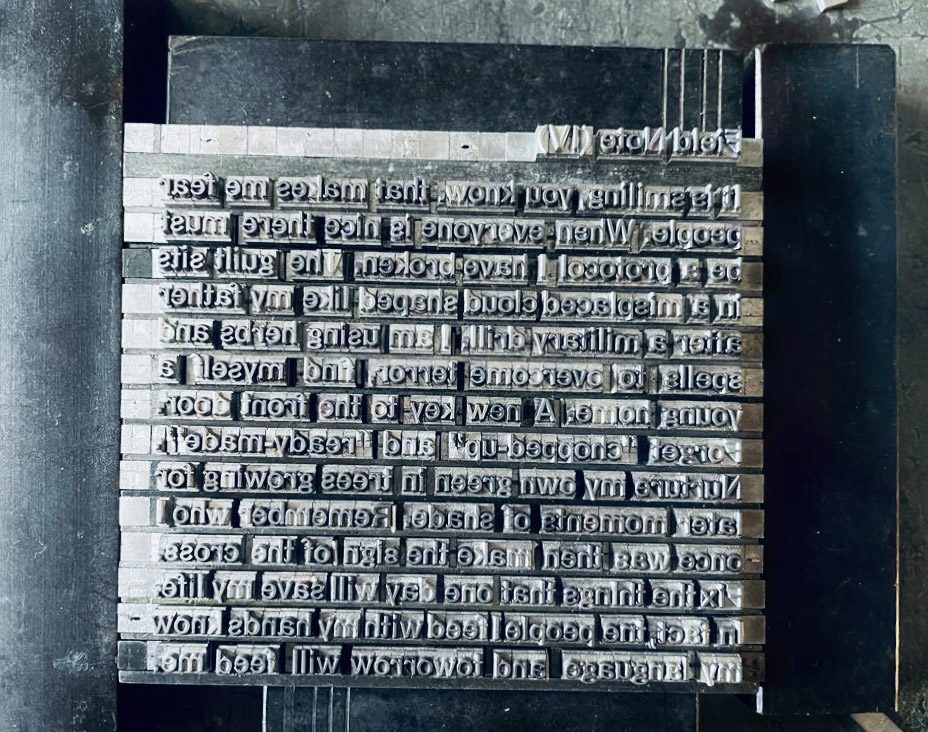

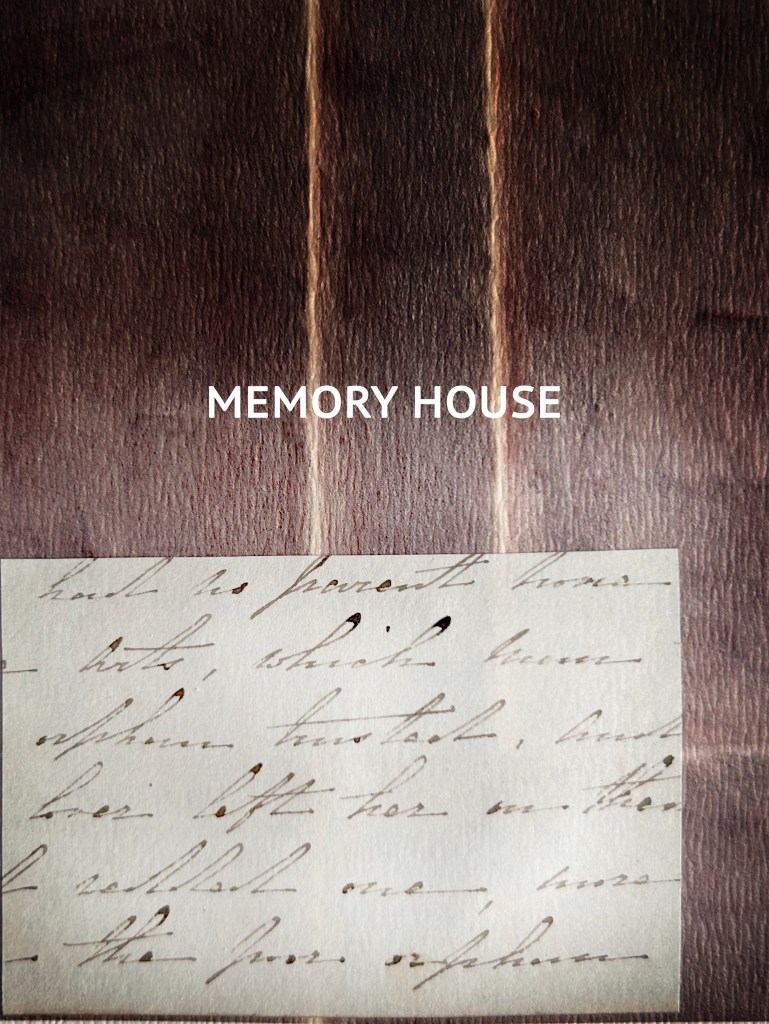

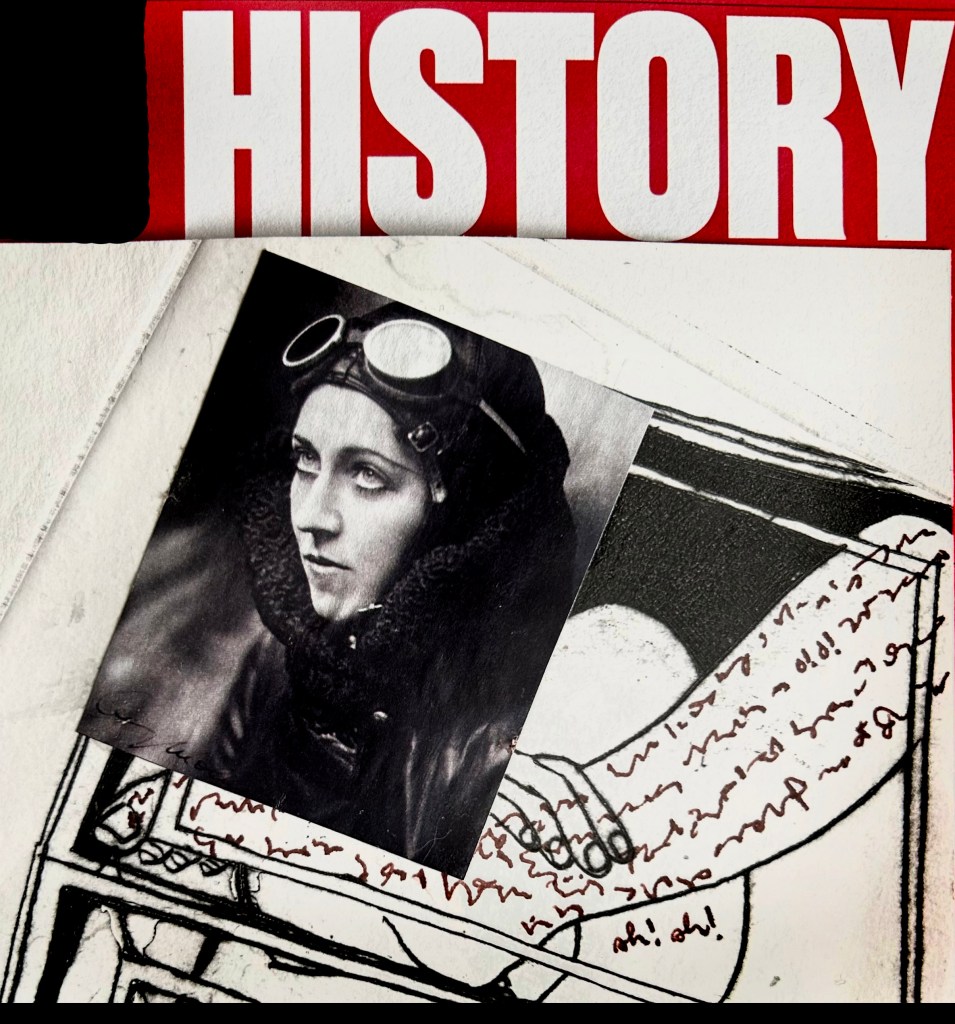

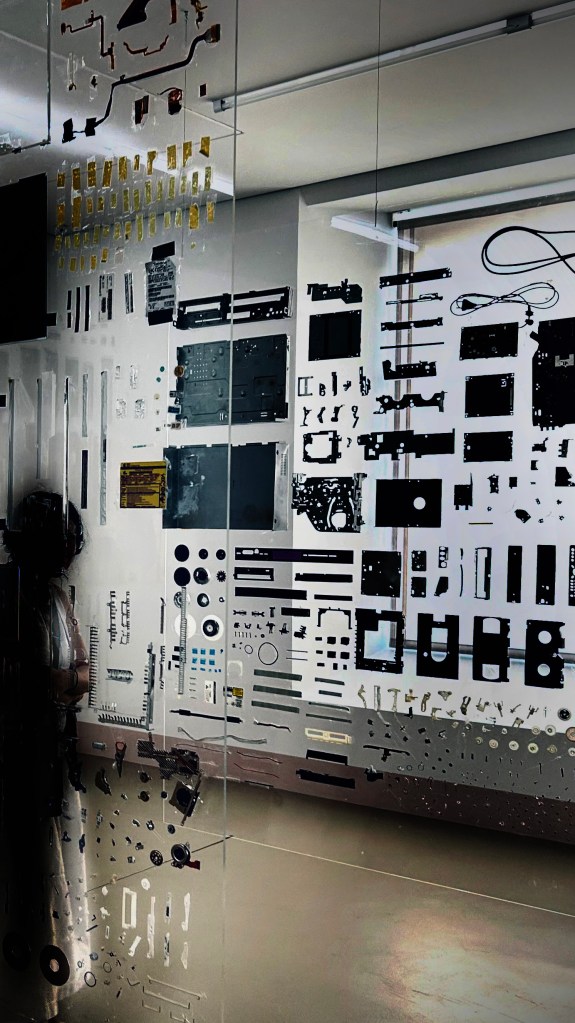

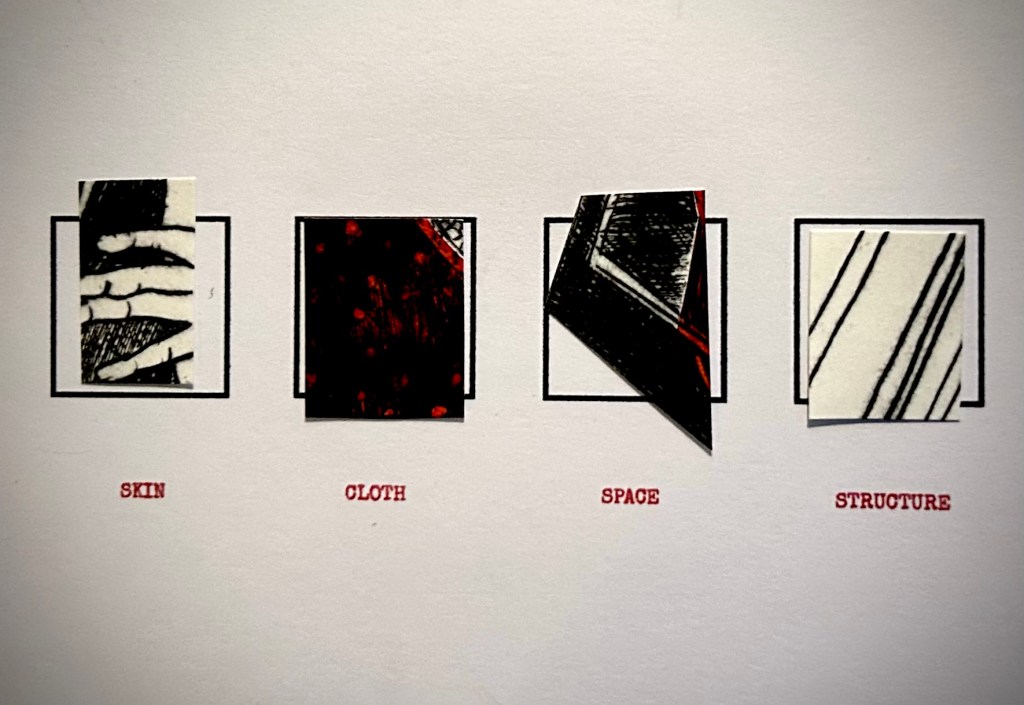

What I mostly remember about the past is a sum of absent encounters, people and things missing; summers, winters, in fact, years melted into a reservoir of images and experiences that are working their way slowly into my future. What I refuse to remember travels along as an indispensable companion to my imagination and my creativity. Understanding this companionship has been one reason for extending my PhD research on the Romanian diaspora in the United Kingdom and collective memory, to build Memøry Høuse. As an art collaboration, Memøry Høuse is searching for a point (or many points) of integrating social memories. Someone recently made me wonder whether this project is a constellation of remembering opportunities. It might possibly be true as not all memories make sense in words. Some are barely perceived in my body, in colour, in sound; or in places and in people. To some extent, my awareness of their existence often frees me from my own enslavement and, as a researcher and writer in this context, the enslavement of the generation I belong to: The Romanian Children of the Decree.

As the Memøry Høuse project evolves, my hope is that these memories will find a place of acknowledgment and, instead of travelling wildly, will begin to settle, find a home, or build their own house on a land that was once foreign but so familiar now.

My gratitude and so many thanks to the artists involved in this collaboration: Mark Mawer and Andrew Morrison.

More updates will follow as the work continues. The exhibition Memøry Høuse will take place in February 2024 at the Lansdown Art Gallery, Stroud.

© Maria Stadnicka, September 2023